If you're looking for help with C#, .NET, Azure, Architecture, or would simply value an independent opinion then please get in touch here or over on Twitter.

Disclaimer: this isn’t really a blog post about Azure but it is quite topical with Windows 10 around the corner and with so many mobile apps making use of Azure in some fashion. I’ve also got a pretty substantial new application almost ready for release into the wild and so in some ways this blog post is a prelude to that – the source code for that app will be available under the MIT License.

With that out the way – I’ve been doing a lot of work with Windows Store apps recently using the WinRT runtime, both converting existing iOS apps to Windows and writing new cross platform apps from the ground up. That’s involved a fair bit of Xaml and although it’s not my first brush with Microsoft’s Xaml family of user interface technologies, indeed one of my favourite roles was working, a few years ago now, as the architect on the Capita SIMS Discover product with a fantastic team. However the last few months is the first time I’ve really had to immerse myself in the Xaml itself – on Discover my hands on work was mostly in the built from scratch data analysis engine and service hosting (and I spent an awful lot of time pretending to be wise!).

Something that always seems to be glossed over by Microsoft in their documentation and developer guides is how to achieve a clean separation between your view models and your Xaml. Although Microsoft often talk about MVC and MVVM most of the patterns in their own examples and tutorials rely on lots of code behind wired up with event handlers. And it’s not clear initially, at least it never was to me, what technology I should use to move away from this mess though fortunately I had one of the UKs best WPF developers – Adam Smith – on hand to point me in the right direction. That being the case when I started working with WinRT I had a reasonable idea of where to head.

A clean separation between the user interface and a domain layer promotes a more testable code base and also allows for a separation of developer and design disciplines (if needed) but if you’re a cross platform app developer using Xamarin to target iOS and Android in addition to Windows then, perhaps even more importantly, getting this separation right is absolutely essential if you want to achieve a high level of code reuse. Which presumably is why you’re using Xamarin in the first place – you’ve been sold on the dream!

In the Xaml WinRT space the key to achieving this are commands and behaviors – and these concepts translate nicely onto the other platforms. I’m going to look at command basics in this post and then follow up with some more advanced concepts and finally I’ll discuss some strategies for dealing with platform specific code.

For the remainder of this post I’m going to assume you have a working knowledge of Xaml, C# and the binding system. The Windows Store Developer site is a good place to start if you’re not. To go along with this post I’ve added a solution to GitHub that contains working examples of everything I’ll discuss. You can find it here.

If you’re reading this then like myself at the same stage in this journey you’ve noticed the word “command” used around the Windows Store developer website, at the time of writing the MSDN developer guide to commanding has this to say on the subject:

A small number of UI elements provide built-in support for commanding. Commanding uses input-related routed events in its underlying implementation. It enables processing of related UI input, such as a certain pointer action or a specific accelerator key, by invoking a single command handler.

If commanding is available for a UI element, consider using its commanding APIs instead of any discrete input events. For more info, see ButtonBase.Command.

You can also implement ICommand to encapsulate command functionality that you invoke from ordinary event handlers. This enables you to use commanding even when there is no Command property available.

Well it’s a start I guess but then the rest of the document proceeds to gloss over this sage wisdom, pushing it to one side like a mouldy sock. I guess it doesn’t look quite so good in a drag and drop coding demo. That’s the final bit of snark – I promise. And it is, to be fair, snark born of well intentioned frustration – Microsoft have a pretty decent UI framework in Xaml but it’s best practice usage is buried away while poor practice usage is pushed massively to the fore and this is a great frustration for me.

Anyway, back on track, what does this boil down to in code? How do we attach a command to a button and have it do something. There is an example of this in the GitHub repository in the BasicCommanding project. This puts a text box and a button on the screen and when you press the button the message changes without an OnClick event handler in sight. First off I start with a view model that looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | public class BasicViewModel : BindableBase { public ICommand UpdateMessageCommand { get; set; } private string _message; public string Message { get { return _message;} set { SetProperty(ref _message, value); } } } |

You can see that we have a property for our update command of type ICommand (the key interface for commands) and a simple message. This derives from a class called BindableBase that deals with the binding notifications for us.

Then our command looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | public class UpdateMessageCommand : ICommand { private readonly BasicViewModel _model; public UpdateMessageCommand(BasicViewModel model) { _model = model; } public bool CanExecute(object parameter) { return true; } public void Execute(object parameter) { _model.Message = "Goodbye!"; } public event EventHandler CanExecuteChanged; } |

This implements the ICommand methods and properties (CanExecute, Execute and CanExecuteChanged) but importantly the constructor takes a reference to an instance of our model and the Execute method updates the message.

Finally we have a few lines of Xaml for bringing this together:

<TextBlock VerticalAlignment="Center" Grid.Column="0" Grid.Row="1" Text="Message"></TextBlock> <TextBox Grid.Column="1" Grid.Row="1" Text="{Binding Message}" IsReadOnly="True"></TextBox> <Button Grid.Column="2" Grid.Row="1" Content="Update message" Command="{Binding UpdateMessageCommand}"></Button> |

You can see that the text of the textbox is bound to our view models message property and the Command property on the button to our command. If you run the sample and click the button you’ll find that, yes, our command is invoked and the message updated and other than associating the view model with the pages data context we have no “code behind” at all.

Furthermore by combining the command with the binding system we don’t get involved in manipulating the user interface directly in our applications domain layer – there is no MyTextBox.Text = “New Value” type code going on and as each such piece of code is a nail in the coffin of cross platform portability that’s rather neat.

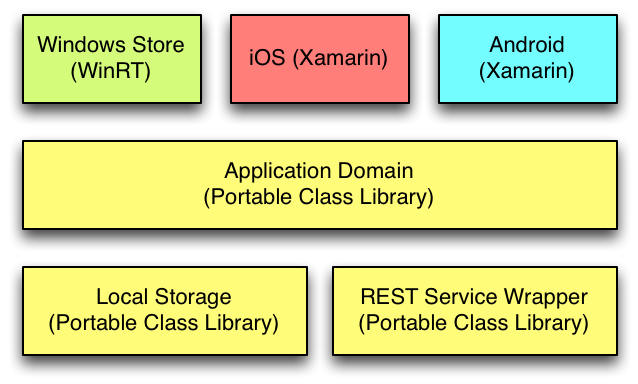

That’s the second time I’ve mentioned a domain layer. In the context of a cross platform application by this I mean a layer that implements all your applications state and business logic via view models, commands, and (where appropriate) interactions with service and storage layers. For a typical cross platform app, and in fact the app I’m working on now looks just like this, you end up with something like this:

Essentially you’re aiming for the thinnest possible layer of platform specific code targetting each platform, below that a domain layer as a portable class library, and it co-ordinating activity between other components of your system such as data access or remote service calls – again with the latter being portable class libraries. Dependencies sometimes means it’s not possible or practical to use portable class libraries end to end without significant work, for example perhaps a significant NuGet package you rely on is only available in native WinRT, iOS and Android form, but in that case you still want to maintain the same kind of structure with different targets but the code staying the same. I’ll cover some of these strategies some other time – the important thing to realise is that commands, view models, and behaviors are key enables of this strategy as they are what allow you to pull your platform specific UI layer away from the rest of your code.

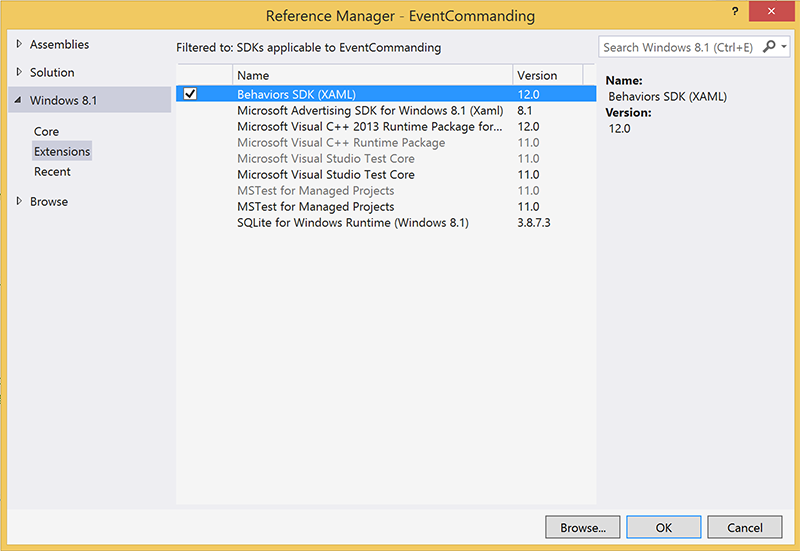

All sounds great so far but the problem you’ll quickly run into is that not all of the controls available to you have a command property and on those that do, such as the Button, how do you handle other events. You can do this by adding the Behaviors SDK in your project. One way to do this is to use the Blend visual design tool but I want to focus on code in this post so staying in Visual Studio add a reference to your project and in the Reference Manager select Windows 8.1 Extensions and then tick Behaviors SDK (XAML) as in the screenshot below:

Amongst other thngs this adds a set of what are known as Behaviors to your project and perhaps the most immediately useful of these is the EventTriggerBehavior. You can attach one or more of these to any control and they will allow you to capture events and handle them through bound commands as in our previous example.

To demonstrate this I have a second example (EventCommanding in the GitHub repository) that changes the text of a TextBlock as you move the pointer over it and out. Without commanding you’d add code to the PointerEntered and PointerExited events. With commands…. well let’s take a look. Here’s the view model for this example, as you can see it’s very similar to the previous view model except there are two commands this time.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | public class BasicViewModel : BindableBase { public ICommand StartCommand { get; set; } public ICommand EndCommand { get; set; } private string _message; public string Message { get { return _message; } set { SetProperty(ref _message, value); } } } |

Our commands look just like our previous command, below is the StartCommand:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | public class StartCommand : ICommand { private readonly BasicViewModel _model; public StartCommand(BasicViewModel model) { _model = model; } public bool CanExecute(object parameter) { return true; } public void Execute(object parameter) { _model.Message = "Move pointer out"; } public event EventHandler CanExecuteChanged; } |

Finally the Xaml below shows how you use the EventTriggerBehavior from the Behaviors SDK to use these commands instead of event handlers in code behind:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | <TextBlock ManipulationMode="All" HorizontalAlignment="Center" VerticalAlignment="Center" Foreground="Red" Text="{Binding Message}" FontSize="18"> <Interactivity:Interaction.Behaviors> <Core:EventTriggerBehavior EventName="PointerEntered"> <Core:InvokeCommandAction Command="{Binding StartCommand}"/> </Core:EventTriggerBehavior> <Core:EventTriggerBehavior EventName="PointerExited"> <Core:InvokeCommandAction Command="{Binding EndCommand}"/> </Core:EventTriggerBehavior> </Interactivity:Interaction.Behaviors> </TextBlock> |

Again in this example we’ve been able to use commands and binding to update our user interface based on user input without any need to reference UI controls directly. It’s easy to see how this approach leads to a clean separation of concerns, better testability, and how we might use these techniques to help us build high code reuse cross platform apps.

In part 2 of this post I’ll cover some more advanced topics about commands and behaviors, for example capturing additional information from events such as in our earlier example the position of the pointer, look at some of the other behaviors in the SDK and take a look at how we can combine them with value converters to further improve our cross platform friendliness.