An anti-pattern I’ve seen a lot over the last few years involves the registration of dependencies in an IoC container at the root of a project (or in a dedicated “IoC” project) – an approach enabled by making every single class in every assembly in the codebase public. It’s amazing how common it is and you see it in codebases that are poor in general and codebases that are otherwise well constructed. As such I find myself talking about it frequently and so it seemed a ripe topic for a blog post.

There are numerous issues with the “every class is public” approach:

- As someone reading or using the code I can no longer differentiate between the public API of a subsystem and the interfaces and classes designed for internal consumption.

- The registering project (for example an ASP.Net application) is making decisions about the lifecycle of components in another assembly and sub-system – and therefore about the internal implementation of that sub-system. This often leads to things getting out of sync and the issues arising from this kind of lifecycle registration / implementation mismatch can be subtle.

- The registering project has to be aware of every single thing in the system and reference every subsystem. One of the effective techniques to police code architecture is by looking at the dependency map and this is heavily polluted if you’re doing this.

- The scope of a code change is often larger than it should be and spans sub-systems when it doesn’t need to – if a project takes the root registration approach then adding a class and interface for internal use means I also have to visit the root project.

- If sub-systems are run within multiple hosts (for example a Web API and a queue processor) then registration is either duplicated in both root projects or an “IoC configuration” project is introduced: we’ve got ourselves in such a pickle that we now need a whole project dedicated to understanding both internal and external dependencies of sub-systems.

Encapsulation is a good thing – it shouldn’t be thrown away when moving from the class to the assembly level. It’s just as important there – perhaps even more so in modern codebases which are formed of many small classes with few methods rather than large classes with many methods.

I’ve provided a simple example of this common issue in the project you can find here:

https://github.com/JamesRandall/IoCAntipatternFix/tree/master/TheProblem

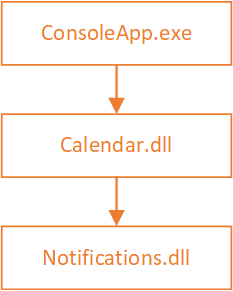

Conceptually in this project we’ve got three assemblies:

- A console app (ConsoleApp) that depends on (2)

- An assembly (Calendar) providing calendar functionality to the console app that depends on (3)

- An assembly (Notifications) providing notification functionality to the calendar assembly

From a required dependency point of view it looks like this:

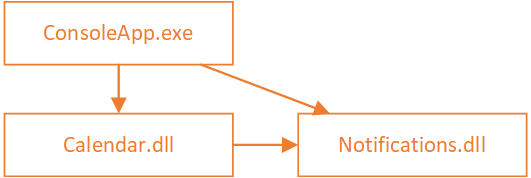

But because of the every class is public issue it is actually implemented like this:

You can see the anti-pattern manifest itself in code in the RegisterDependencies method of Program.cs in the console app:

static IServiceProvider RegisterDependencies()

{

IServiceCollection services = new ServiceCollection();

services.AddTransient<Calendar.DataAccess.ICalendarRepository, Calendar.DataAccess.CalendarRepository>();

services.AddTransient<Calendar.ICalendarManager, Calendar.CalendarManager>();

services.AddSingleton<Notifications.INotifier, Notifications.Notifier>();

services.AddTransient<Notifications.Channel.IEmail, Notifications.Channel.Email>();

return services.BuildServiceProvider();

}

Does the console app have any business knowing that the ICalendarRepository is implemented by the CalendarRepository class? Should it even know about the email channel? Can it safely register the INotifier implementation as a singleton? The answer to all of those questions is no. Absolutely not.

The fix for this is pretty simple and it was great to see Microsoft adopt a version of it in ASP.Net Core as part of their formalisation of dependency inversion in that framework. All you need do is encapsulate the registration logic inside your sub systems – and if you need to conditionally configure the registration then pass through an options block (an example of this can be seen in my commanding framework).

I’m going to show two versions of the fix – one based on using the containers registration interface, which has the byproduct of your assemblies becoming tied to an IoC container, and another that doesn’t require this.

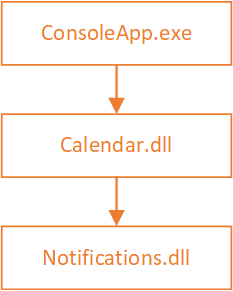

Solution with a container interface

The approach adopted by Microsoft in the ASP.Net Core assemblies and the related packages is to use extension methods on the container interface (in the Microsoft case that’s IServiceCollection). If we take this approach the registration in our console app now looks like this:

static IServiceProvider RegisterDependencies()

{

IServiceCollection services = new ServiceCollection();

services.AddCalendar();

return services.BuildServiceProvider();

}

Additionally our console app no longer has a reference to the notification sub-system as this is now dealt with by the calendar’s AddCalendar registration method:

public static class ServiceCollectionExtensions

{

public static IServiceCollection AddCalendar(this IServiceCollection serviceCollection)

{

serviceCollection.AddTransient<ICalendarRepository, CalendarRepository>();

serviceCollection.AddTransient<ICalendarManager, CalendarManager>();

serviceCollection.AddNotifications();

return serviceCollection;

}

}

Inside the calendar project only the interfaces intended for external consumption are marked as public with the rest moving to internal. It’s no longer possible to access the assemblies private implementation from the outside and we’ve moved the lifecycle and registration logic closer to the code that is written in line with those expectations.

And finally the notification assembly takes the same approach:

public static class ServiceCollectionExtensions

{

public static IServiceCollection AddNotifications(this IServiceCollection serviceCollection)

{

serviceCollection.AddSingleton<INotifier, Notifier>();

serviceCollection.AddTransient<IEmail, Email>();

return serviceCollection;

}

}

With this approach we’ve addressed all three of the concerns I raised at the start of this piece and have moved back to a place where encapsulation is used to help us both read the code and use it safely.

It could well be argued that having your sub-systems reference and be aware of the specific IoC container in use is itself another anti-pattern. I’d tend towards agreeing but it can be a pragmatic choice for an internal codebase – though it’s flawed if you are creating packages for others to use: you’ve built in a hard dependency on a specific IoC container. You can solve this by defining your own interface for proxying over a container and having people implement it or use a functional approach which we’ll look at next.

The code for the above approach can be found here:

https://github.com/JamesRandall/IoCAntipatternFix/tree/master/ContainerInterfaceSolution

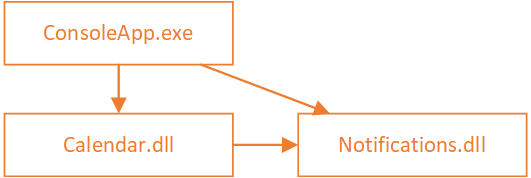

Solution with functions

An alternative to the interface approach is to use a functional style passing down lambda expressions. If we take this approach our console application’s registration method now looks like this:

static IServiceProvider RegisterDependencies()

{

IServiceCollection services = new ServiceCollection();

Dependencies.AddCalendar(

(iface, impl) => services.AddTransient(iface, impl),

(iface, impl) => services.AddSingleton(iface, impl));

return services.BuildServiceProvider();

}

We simply wrap the relevant lifecycle registration methods on IServiceCollection inside lambda expressions and pass them down to a registration method in our calendar sub system:

public static class Dependencies

{

public static void AddCalendar(

Action<Type, Type> addTransient,

Action<Type, Type> addSingleton)

{

addTransient(typeof(ICalendarRepository), typeof(CalendarRepository));

addTransient(typeof(ICalendarManager), typeof(CalendarManager));

Notifications.Dependencies.AddNotifications(addTransient, addSingleton);

}

}

This registers our types using the lambda expressions and passes them on to the notification dependency:

public static class Dependencies

{

public static void AddNotifications(

Action<Type, Type> addTransient,

Action<Type, Type> addSingleton)

{

addSingleton(typeof(INotifier), typeof(Notifier));

addTransient(typeof(IEmail), typeof(Email));

}

}

Again this approach addresses the concerns that arise when implementation classes are made public and registration is centralised but with the added advantage that the sub-systems are independent of any specific IoC container. In my experience this also discourages people from misusing many of the “advanced” capabilities that can be found on IoC containers – but that’s a topic for another post.

The code for this approach can be found here:

https://github.com/JamesRandall/IoCAntipatternFix/tree/master/FunctionalSolution

Wrap up

Hopefully in the above I’ve highlighted a common pitfall and demonstrated two solutions to it. There are of course many other variants you can apply depending on your specific project. If you disagree or have any questions please feel free to reach out on Twitter.

Recent Comments