If you follow me on Twitter you might have seen that as a side project I run a cycling performance analytics website called Performance For Cyclists – this is currently running on Azure.

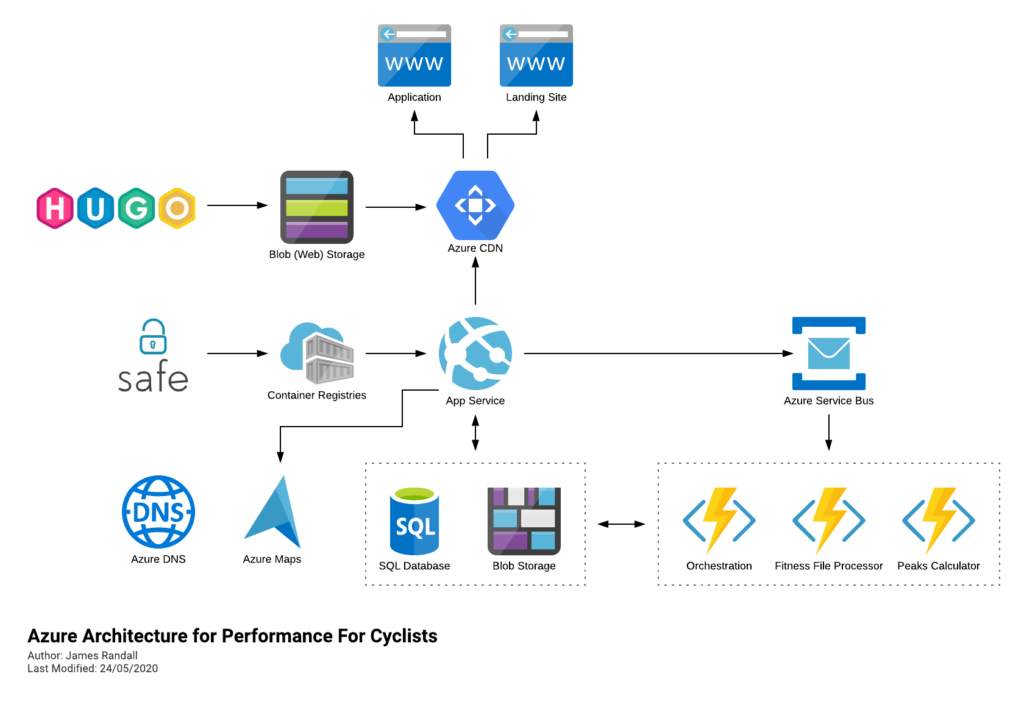

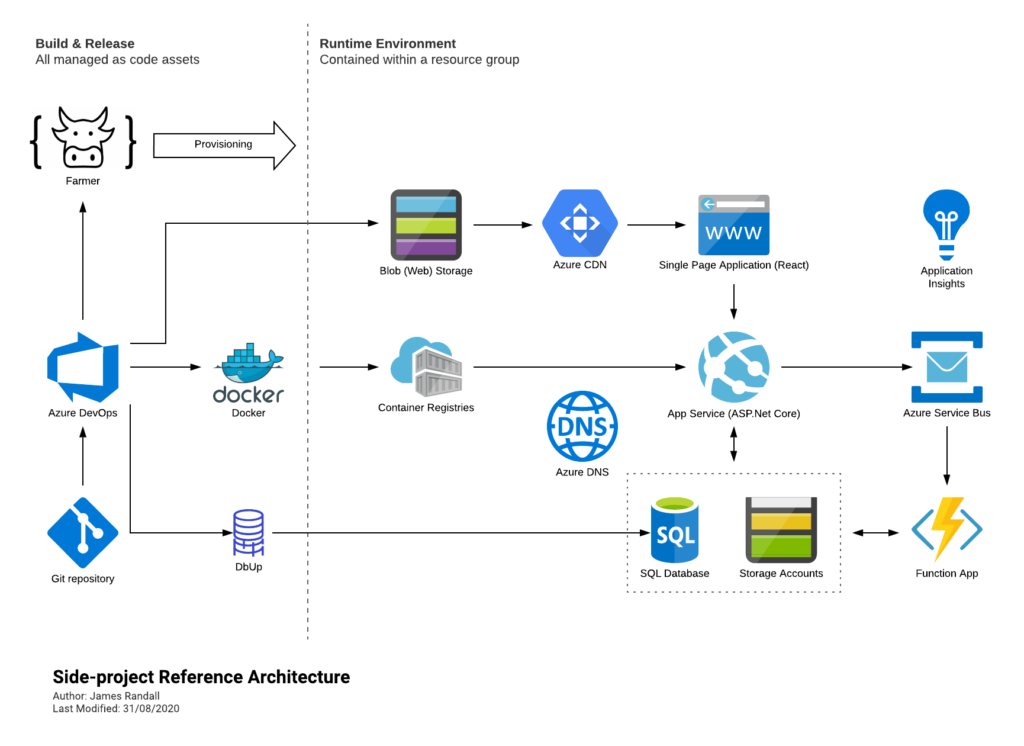

Its built in F# and deploys to Azure largely like this (its moved on a little since I drew this but not massively):

It runs fine but if you’ve been following me recently you’ll know I’ve been looking at AWS and am becoming somewhat concerned that Microsoft are falling behind in a couple of key areas:

- Support for .NET – AWS seem to always be a step ahead in terms of .NET running in serverless environments with official support for the latest runtimes rolling out quickly and the ability to deploy custom runtimes if you need. Cold starts are much better and they have the capability to run an ASP.Net Core application serverlessly with much less fuss.

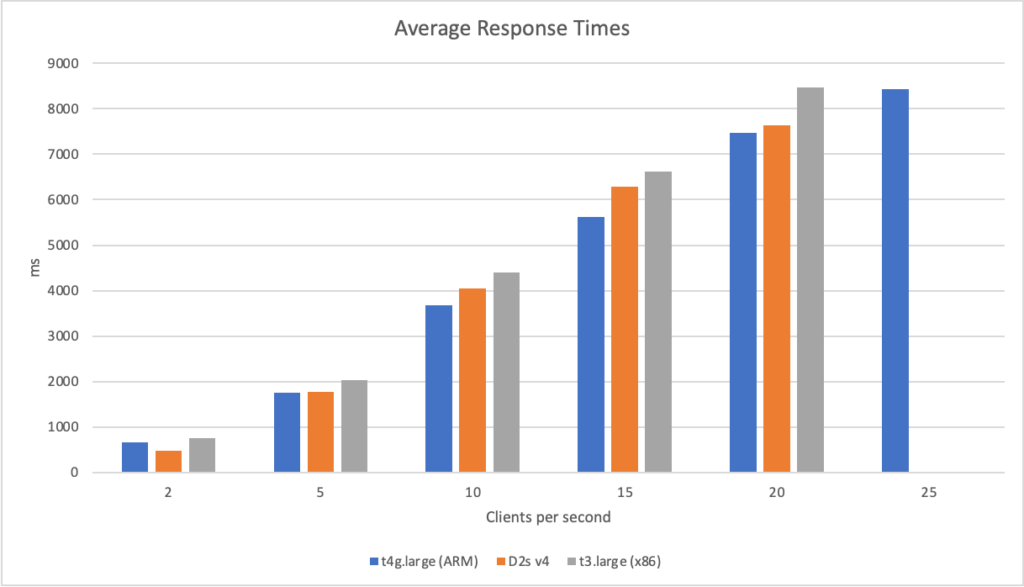

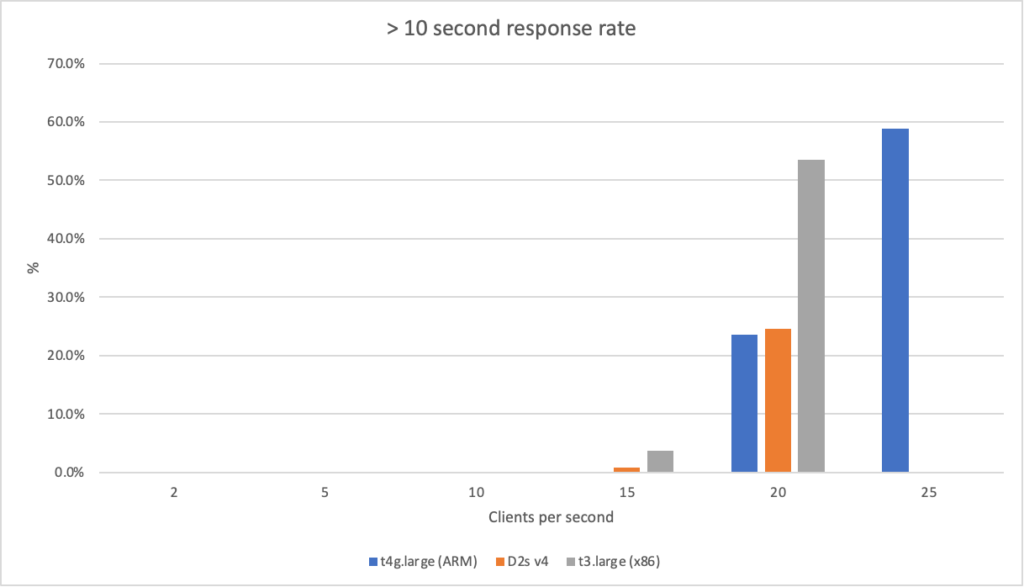

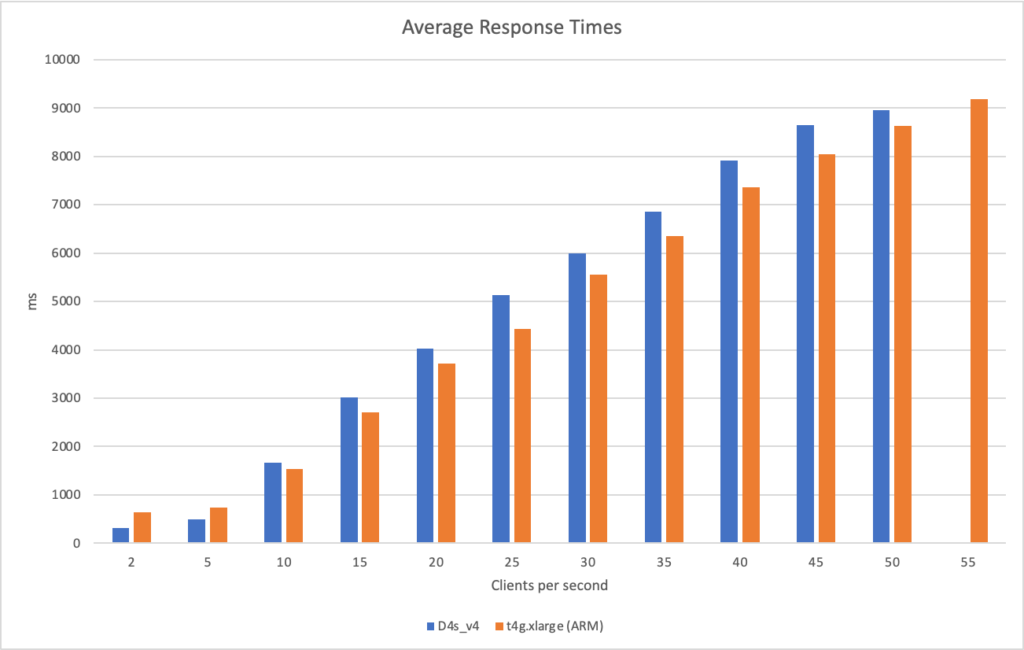

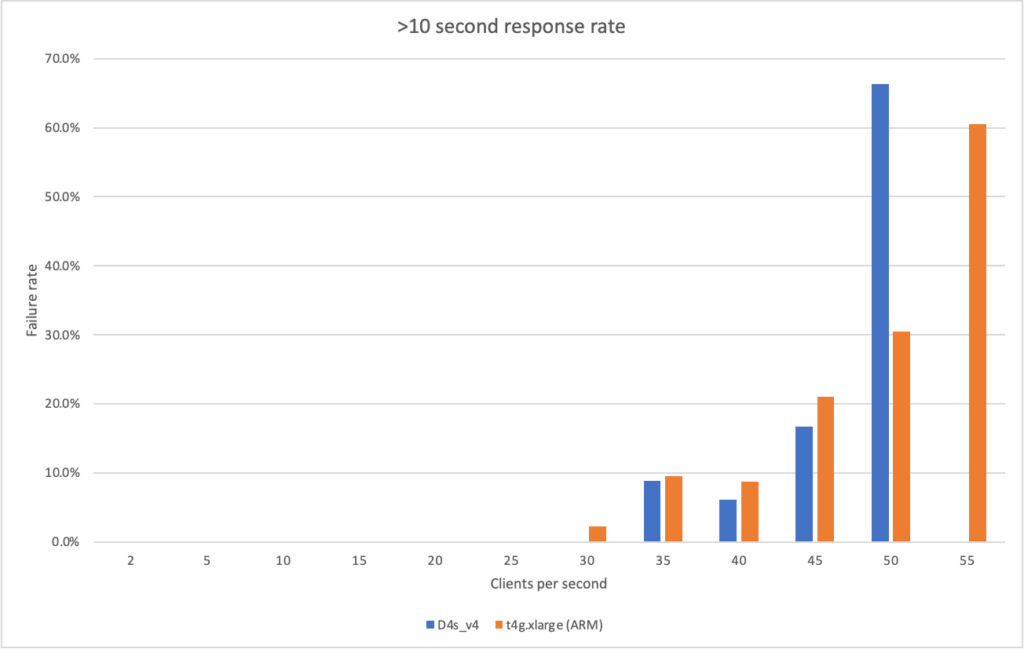

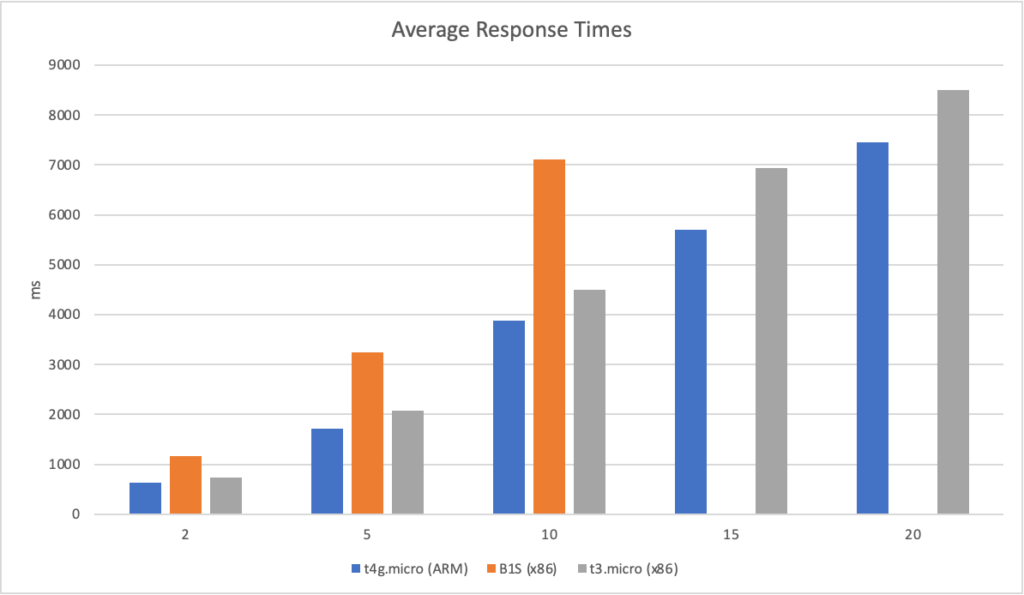

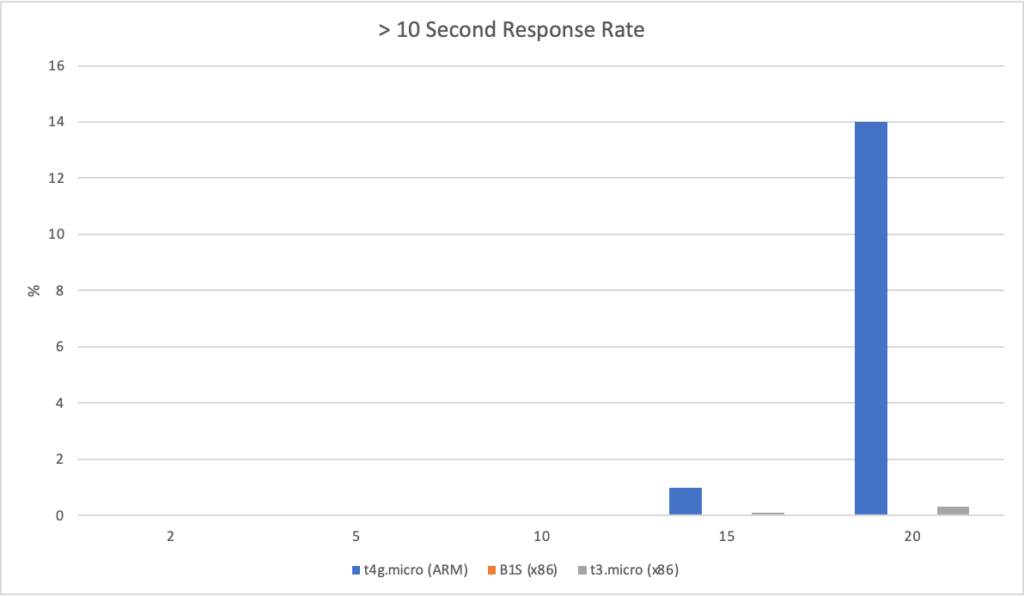

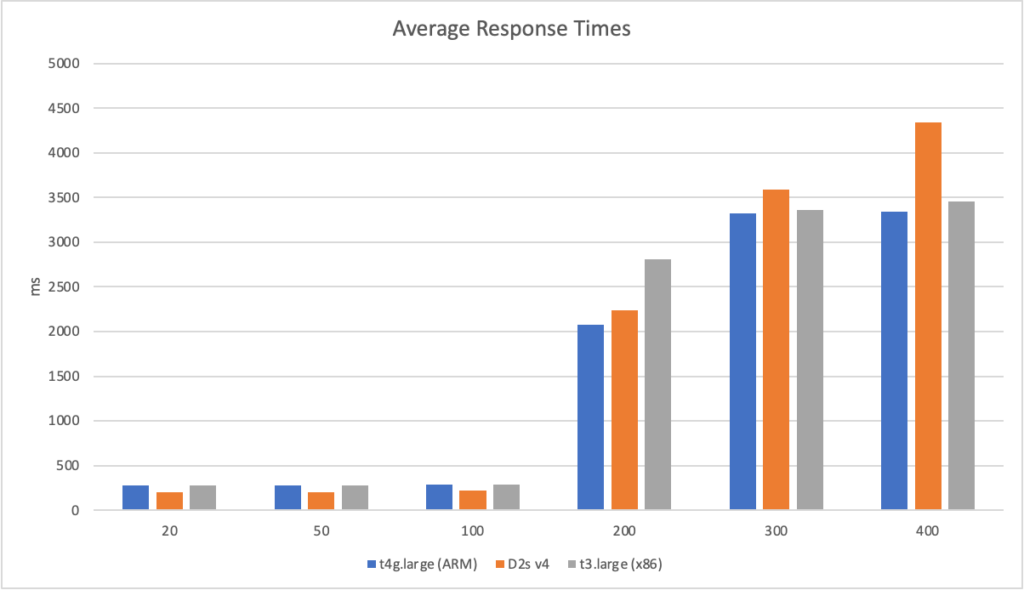

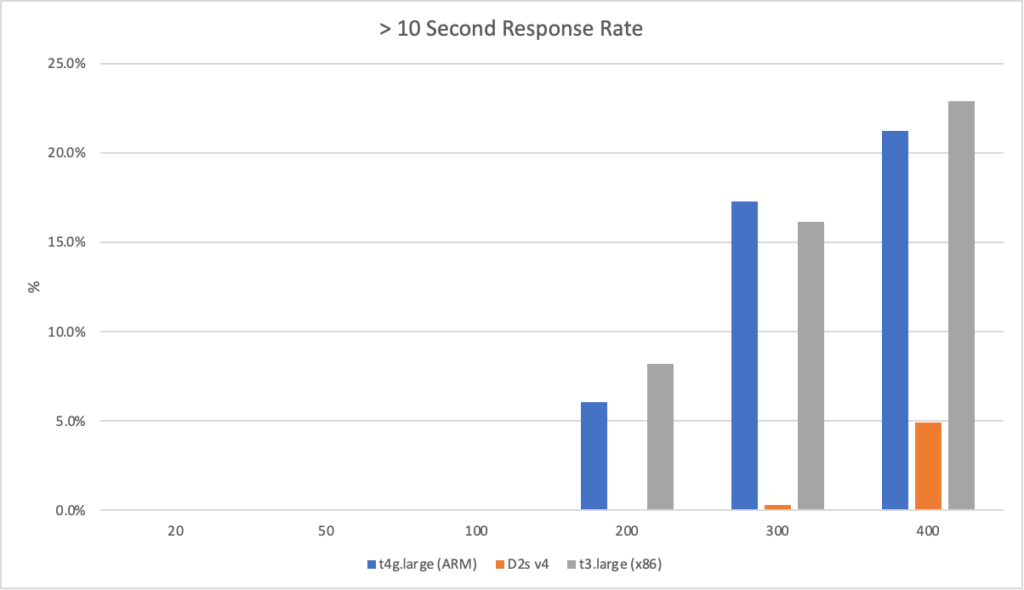

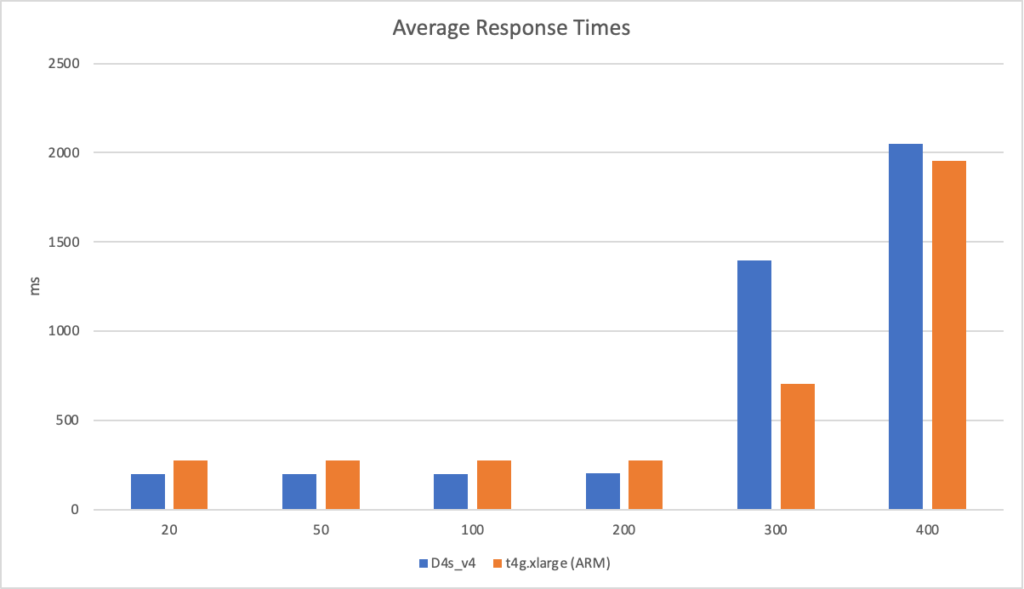

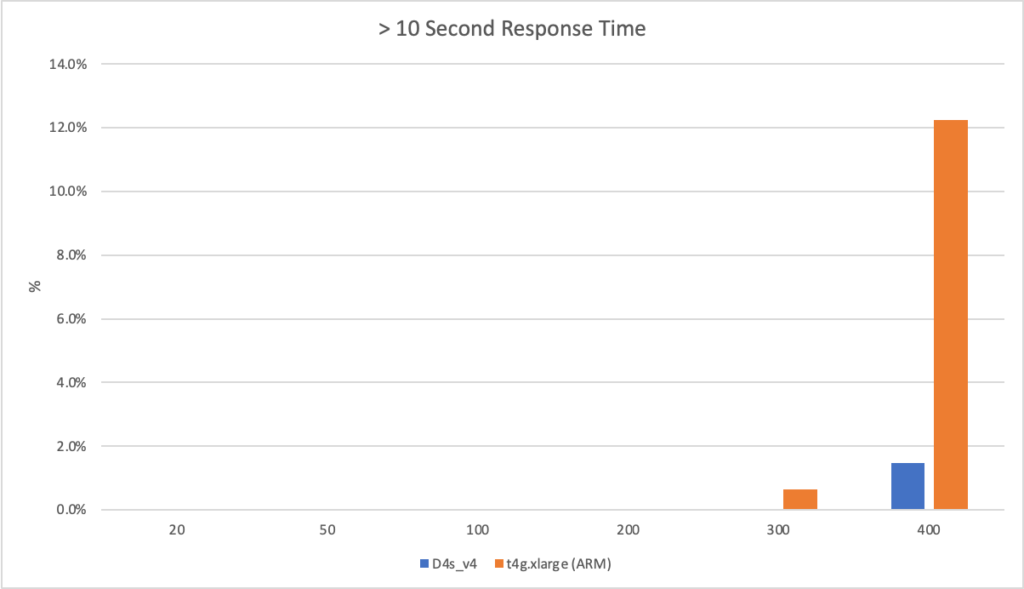

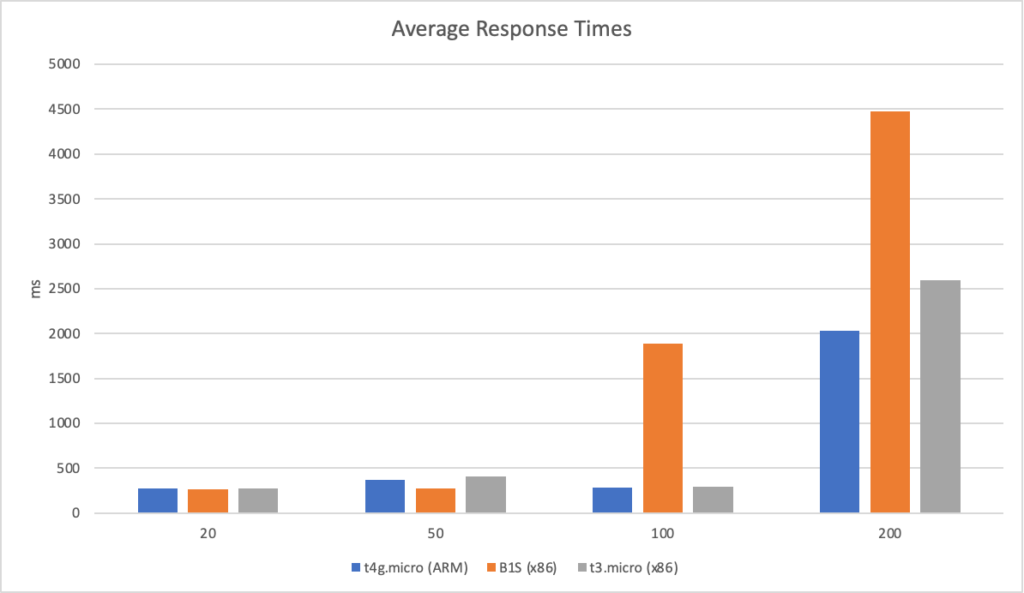

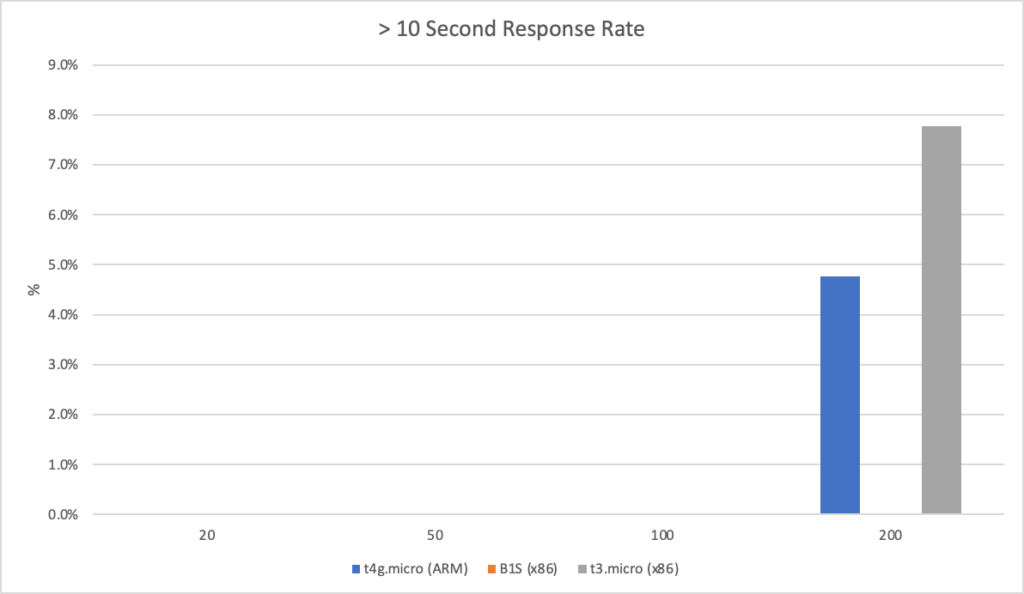

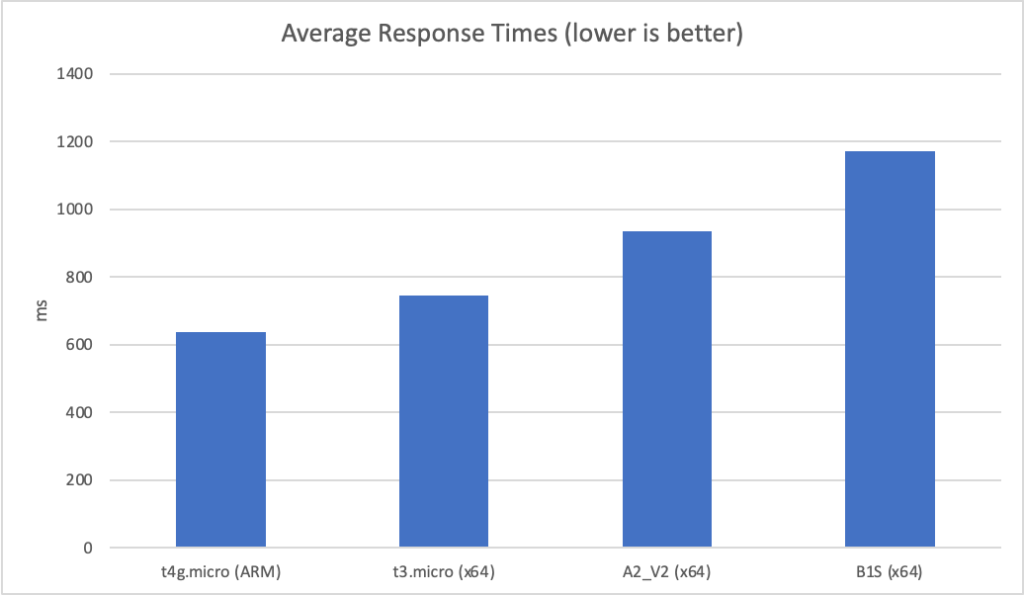

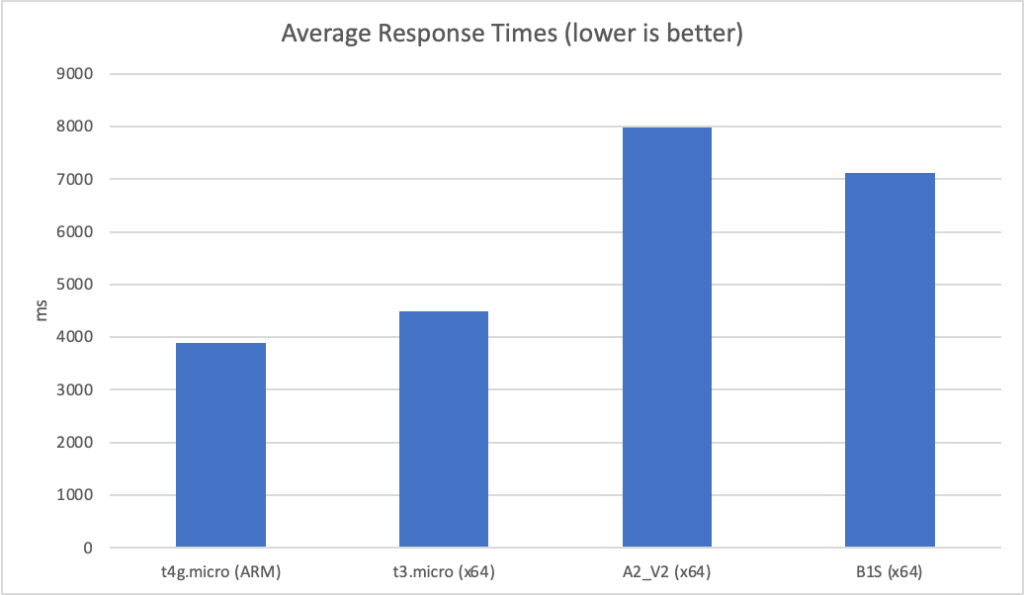

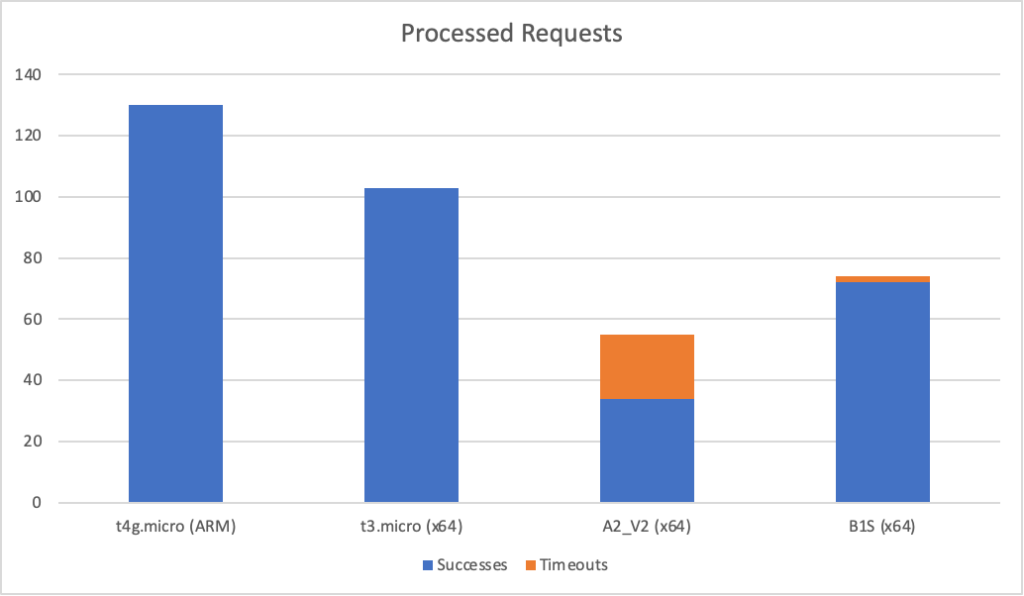

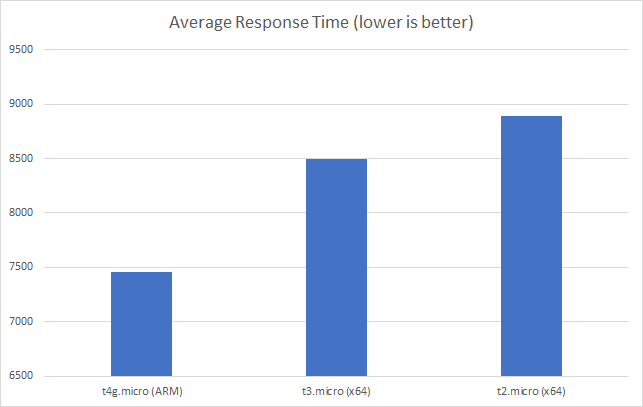

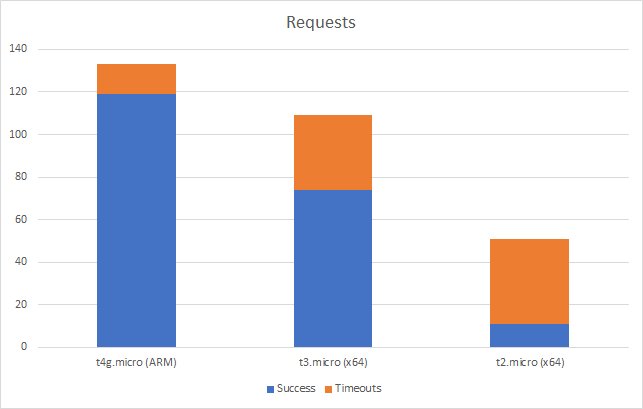

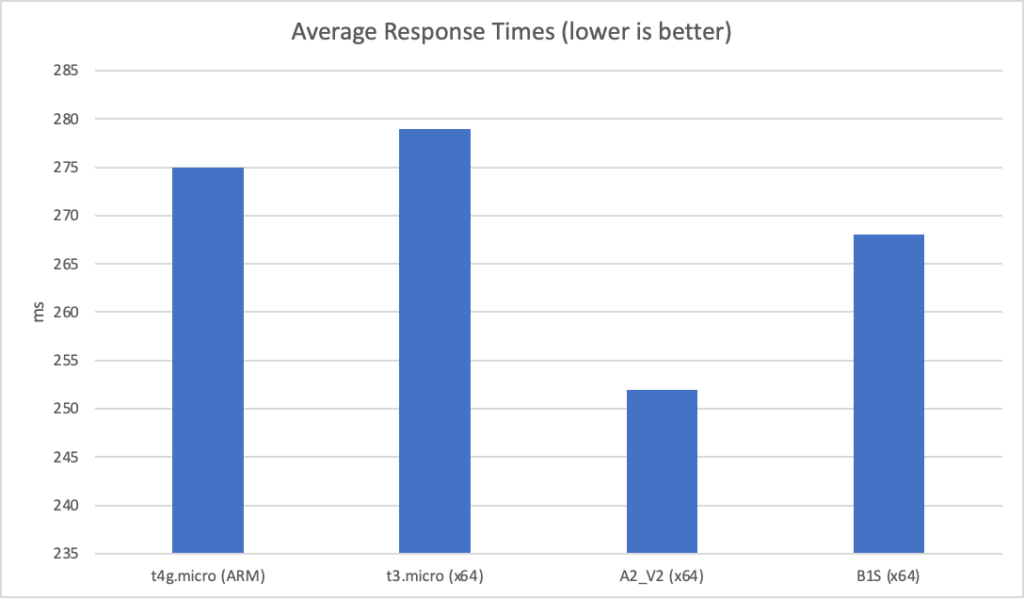

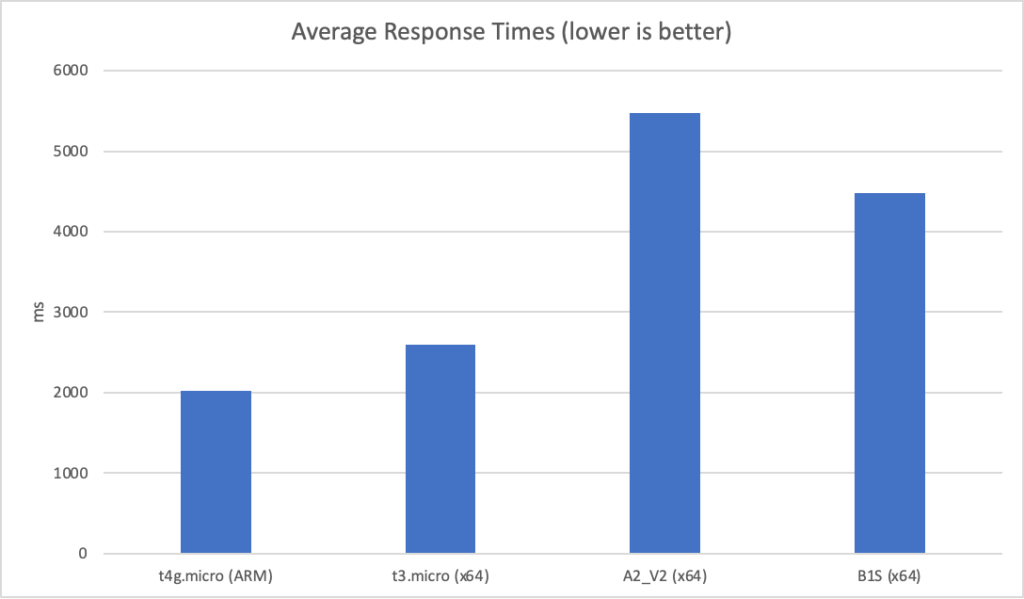

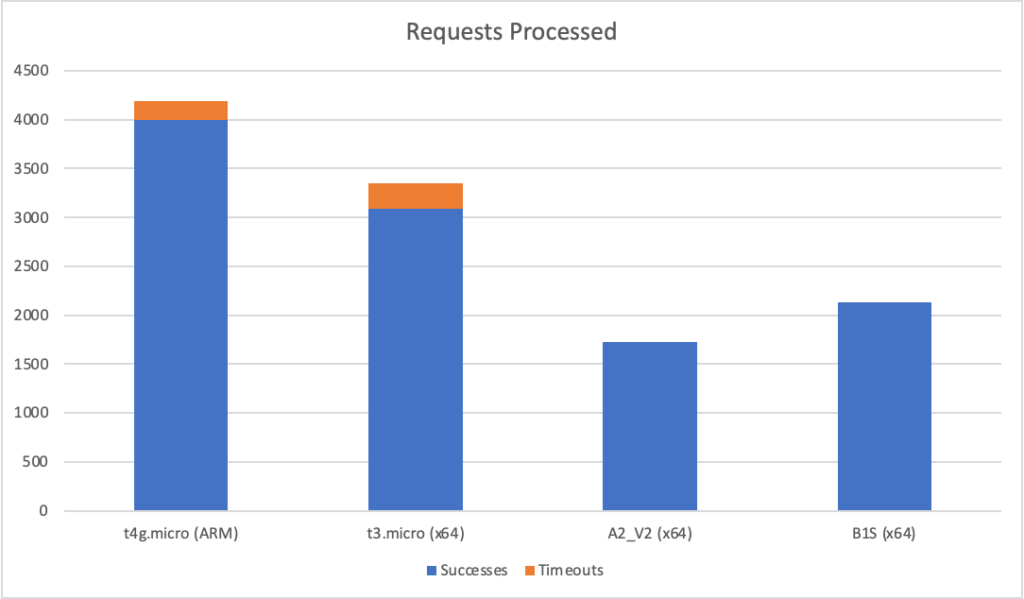

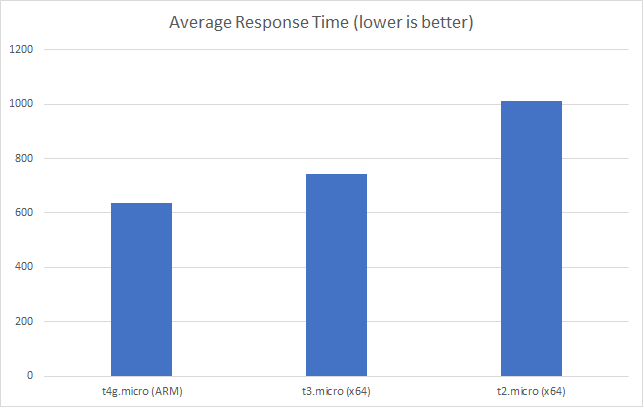

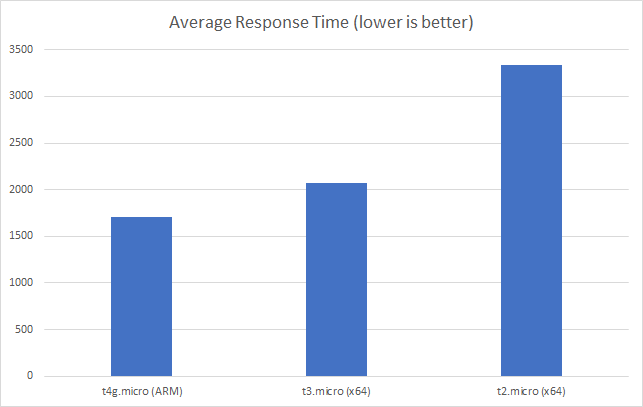

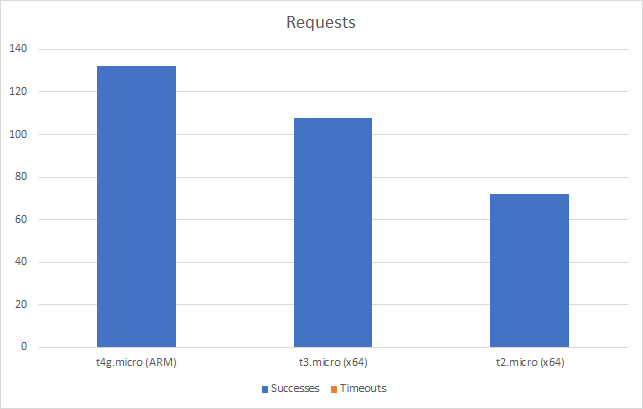

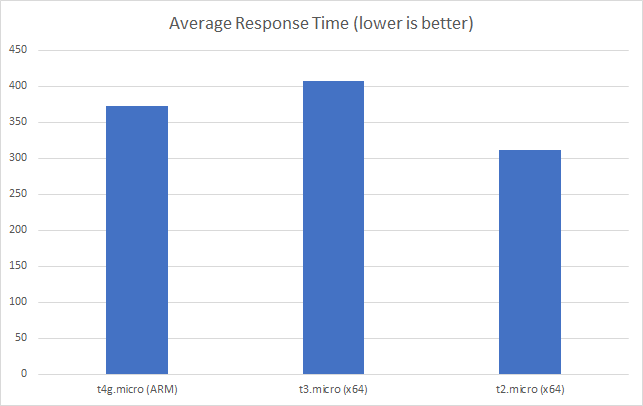

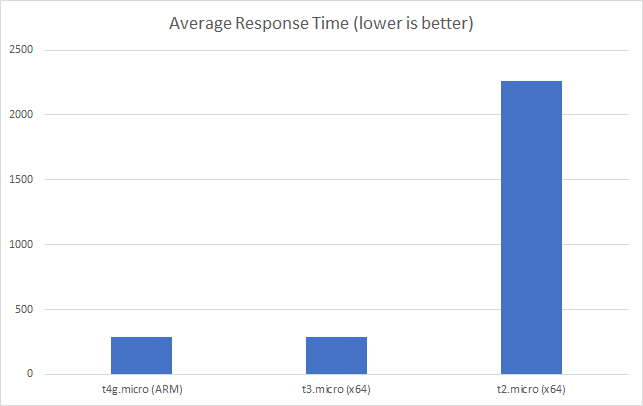

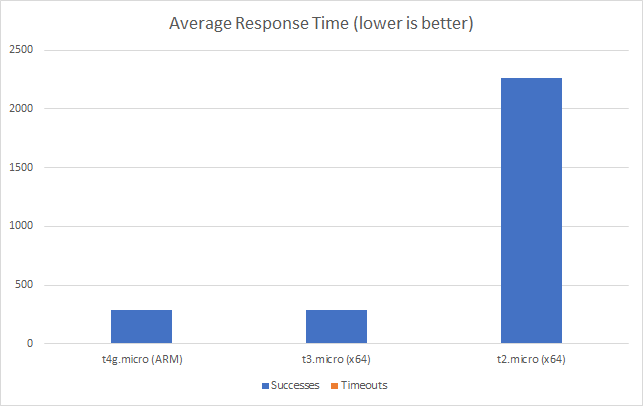

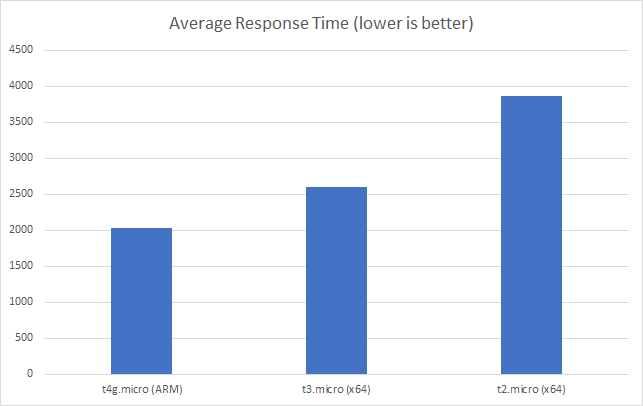

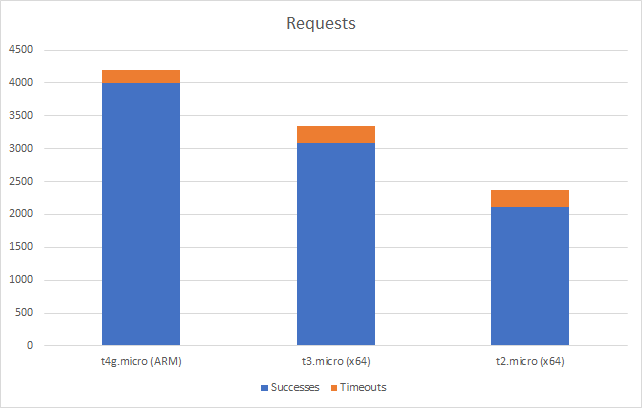

I can also, already, run .NET on ARM on AWS which leads me to my second point (its almost as if I planned this)… - Lower compute costs – my recent tests demonstrated that I could achieve a 20% to 40% saving depending on the workload by making use of ARM on AWS. It seems clear that AWS are going to broaden out ARM yet further and I can imagine them using that to put some distance between Azure and AWS pricing.

I’ve poked around this as best I can with the channels available to me but can’t get any engagement so my current assumption is Microsoft aren’t listening (to me or more broadly), know but have no response, or know but aren’t yet ready to reveal a response.

(just want to be clear about something – I don’t have an intrinsic interest in ARM, its the outcomes and any coupled economic opportunities that I am interested in)

I’m also just plain and simpe curious. I’ve dabbled with AWS, mostly when clients were using it when I freelanced, but never really gone at it with anything of significant size.

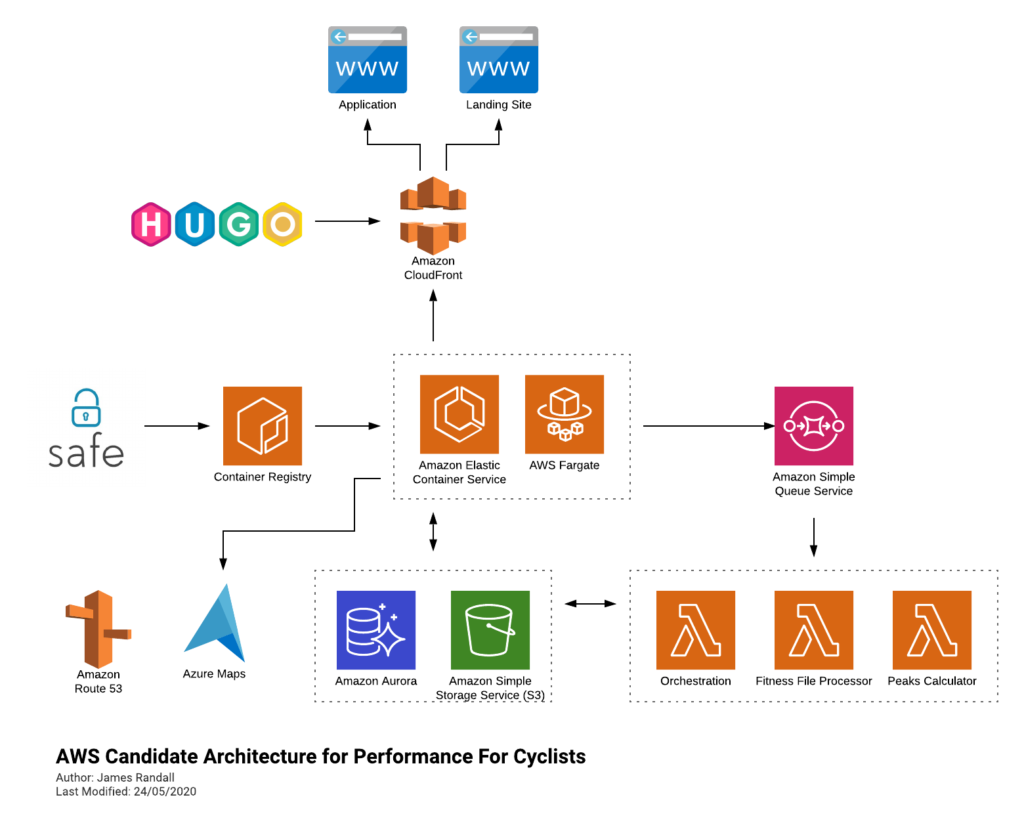

I’m going to have to figure my way through things a bit, and doubtless iterate, but at the moment I’m figuring its going to end up looking something like this:

Leaving Azure Maps their isn’t a mistake – I’m not sure what service on AWS offers the functionality I need, happy to here suggestions on Twitter!

I may go through this process and decide I’m going to stick with Azure but worst case is that I learn something! Either way I’ll blog about what I learn. I’ve already got the API up and running in ECS backed by Fargate and being built and deployed through GitHub Actions and so I’ll write about that in my next post.

Recent Comments